John Hancock (1737-1793)

John Hancock was a major political leader in the era of the American Revolution, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and president of the Continental Congress.

Hancock was born in Braintree, Massachusetts, in 1737, and educated at Boston's Latin School and Harvard. From an uncle he inherited Boston's leading mercantile firm and almost overnight became one of the wealthiest men in New England. His passion, however, was not for business but for politics and he was elected to the Massachusetts Assembly just as news of Parliament's passage of the Stamp Act become common knowledge in America. Although neither a great orator, like Patrick Henry, nor a remarkable writer, like James Otis, he engaged in a more personal style of political leadership in his opposition to the British government's colonial policies of the 1760s. In June 1768 those policies touched him directly when his ship, the Liberty, was confiscated by the Board of Customs Commissioners (created by the Townshend Acts), for suspicion of smuggling Madeira wine. That the evidence suggests the smuggling charges were probably true made no difference to Boston patriots who rallied to Hancock's defense. Several thousand Bostonians attacked the homes of the customs commissioners, beat up a customs inspector, and burned a boat belonging to one of the customs collectors on the Boston Common, in front of Hancock's house. John Adams successfully defended Hancock against prosecution for smuggling; during the case he made the argument that paying duties on the wine was unconstitutional in the first place because it represented a tax levied by Parliament "without our Consent."

Over the next several years, Hancock's commitment to the radical opposition in Boston deepened, even though he was courted by the governor with an appointment to his Council and promotion in the militia, among other favors. In March 1774, on the fourth anniversary of the Boston "Massacre," his patriot credentials were sealed when he was selected to deliver the annual address to commemorate those slain. After speaking of his attachment to righteous government and hatred of tyranny to the "vast concourse of people" assembled at the Old South Meeting House, he observed:

the troops of George the third have crossed the Atlantic, not to engage an enemy, but to assist a band of traitors in trampling on the rights and liberties of his most loyal subjects; those rights and liberties, which, as a father, he ought ever to regard, and as a king, he is bound in honour to defend from violation, even at the risk of his own life.

The Boston Gazette noted that Hancock's remarks were received with "universal applause." Not chosen as a delegate to the First Continental Congress (for unknown reasons), Hancock was therefore in Massachusetts rather than Philadelphia in September 1774 when he presided over a "Provincial Congress" that met without the approval of the new military governor of the colony, Major General Thomas Gage. In October it warned Gage that he was leading them to "the confusions and horrors of a civil war," directed that all future provincial taxes be paid to colonial officers, not those of the Crown, and appointed a committee recommending steps to place Massachusetts in a posture of defense. By then, Hancock, Adams, and several others were found by Britain's attorney general and solicitor general to be "chargeable with the crime of high treason."

In 1775, Hancock continued as president of the Provincial Congress, was appointed to its Committee of Safety, and was selected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. In February, the Provincial Congress gave the committee authority over all military supplies in the colony, a move that especially alarmed Gage (and set the stage for his attempt to seize those supplies in April). In January, the Secretary of State for the Colonies wrote Gage that the "principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress" should be arrested for treason, but he left the decision of whether to proceed entirely in Gage's hands. It must be noted that there is no evidence that a proper warrant was issued for Hancock's (or Adams') arrest or, as some historians have contended, that the Administration of Justice Act of 1774 (one of the Coercive Acts) singled out the two to be taken to Britain for trial. (Gage did, however, after the fighting began, expressly exempt only Hancock and Adams from his June 1775 offer of pardon to all those who had taken up arms). Nevertheless, fictional "orders" for their imprisonment were confidently printed in colonial newspapers, which gave rise to very real fears, although they did not seem to cause Hancock and Adams to flee Boston. Rather, meetings of the Provincial Congress in Cambridge and Concord kept them out of town for stretches. In late March 1775, after a meeting of the congress in Concord, the two decided to sojourn at Hancock's grandfather's house in Lexington, where Hancock's wife, Dorothy Quincy, was staying. There is no evidence that Gage's subsequent attempt to capture the arms at Concord included an explicit attempt to arrest Adams and Hancock, although Gage was authorized to take into custody any of the provincial opposition leaders who fell in his way, which, given the location of the house where the two were staying (right on the road from Lexington to Concord), they almost literally did. Hancock himself believed that he was "on the spot" of the opening clash of the War for Independence only by luck. In any event, both Paul Revere and William Dawes gave Hancock and Adams ample warning of Gage's advance in the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, leaving them plenty of time to shift to Woburn. Three days later they both departed for Philadelphia and the meeting of the Second Continental Congress.

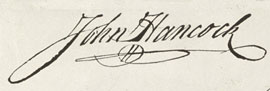

When Peyton Randolph, the president of the First and Second Continental Congress, left Philadelphia in May 1775 for a session of Virginia's House of Burgesses, Hancock was elected unanimously to succeed him. Benjamin Harrison, a delegate from Virginia, described Hancock in July 1775 as "Noble, Disinterested & Generous to a very great Degree." Randolph might have felt similarly because on his return to the Congress in August, he did not attempt to reclaim his position (he was also very ill and died on October 22, 1775). Hancock remained president of the body until 1777. He therefore presided over the passage of the resolution for independence; the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, on which his signature is the most prominent; and the creation of the Articles of Confederation. Hancock then returned to Massachusetts, where he commanded state forces, served in the legislature (including a stint as its speaker), and was a member of the state constitutional convention. In 1780, he was elected the state's first governor under its new constitution, an office that he held until 1785 and then again from 1789 until his death in 1793. He was also a member of Massachusetts' convention to ratify the federal constitution of 1787 and played an influential role in its adoption.

Hancock died on October 8, 1793.