The War for Independence, through Saratoga

The Declaration of Independence dramatically transformed the armed conflicts that began in 1775. Battles at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, Great Bridge in Virginia, and even the Siege of Boston, can all be seen as insurgencies against the British government until July 2, 1776, when conciliation went from improbable to impossible as the fighting became an all—out War for Independence.

British strategy at the beginning of the war focused on northern colonies. After their evacuation of Boston on March 17, 1776, the British shifted their considerably reinforced attention to New York in order to cut New England off from the rest of the colonies. British commanders, led by Major General Thomas Howe, planned to advance through New York by land and sea, capturing New York City in the east while another army moved its way into northern New York from Canada towards an eventual link of the two forces.

The campaign in the east went well for the British. Howe captured New York City (which the British would hold for the rest of the war) with relative ease, although he allowed George Washington's army to escape. He also secured the major port of Newport, Rhode Island, and occupied much of northern New Jersey. Despite relatively minor defeats in New Jersey at Trenton on December 25, 1776, and at Princeton on January 3, 1777, Howe was able to considerably expand Britain's zone of occupation in September 1777 when he attacked southeastern Pennsylvania, inflicting a significant defeat on Washington at Brandywine, on September 11, 1777, allowing Howe to capture Philadelphia on September 26. Congress was forced to flee to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, then further west to York. With Congress in flight, Washington's army driven off, and the British in command of three of America's five largest ports, it seemed to many that American independence was doomed.

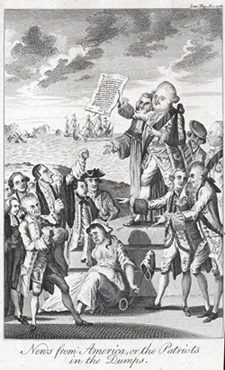

That all changed in October 1777 when the British army moving into New York from Canada, under the command of Major General John Burgoyne, was forced to surrender at Saratoga, New York. While the capture of almost 6,000 troops was a significant enough blow to British strategy and boost to American spirits, the diplomatic consequences of Burgoyne's defeat were even more consequential as it brought France, and then Spain, into the war on America's side. Although the French had clandestinely assisted the Americans with weapons, ammunition, and other supplies almost from the beginning of the conflict, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (promoting trade) and the Treaty of Alliance (establishing a military partnership) between the United States and France were both signed on February 6, 1778 — only two months after news of Saratoga reached Paris.

On February 17, 1778, Parliament appointed its first peace commission to attempt to negotiate an end to the war. More significantly, and extraordinarily, on March 18, 1778, Parliament repealed the acts that the former colonials found most offensive — the Tea Act and the Coercive Acts, among others — and passed a new Declaratory Act that explicitly renounced Parliament's right to tax the colonies without their consent, capitulating on the constitutional issue that had driven Americans to revolution in the first place.