Williamsburg and the Intercolonial Committees of Correspondence

By January 1773 the Virginia Gazette had carried the news of the Gaspée Commission's power to turn evidence and suspects over to imperial officials for transport to England for trial. On February 4, Richard Henry Lee wrote to Samuel Adams for the first time and asked for an accurate report of the affair since he felt the newspapers were an "uncertain medium." A week later Lee was certain that the story of the latest invasion of British American rights was true and promised Thomas Cushing, the Crown's Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, that he would make sure the House of Burgesses addressed the matter at its next session in March.

When Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, George Washington, and the rest of the burgesses began the trek to Williamsburg at the end of February, the taverns were alive with more than just talk of the Gaspée affair. In January, the colony's treasurer, Robert Carter Nicholas, learned that notes and coins had been counterfeited and were circulating throughout Virginia, threatening to bring commerce, already slowed by the Credit Crisis of 1772, to a halt. Acting on the advice of his council, Virginia's governor, the earl of Dunmore, called the Assembly into session to fix the problem and restore public confidence in the Virginia economy. When Dunmore learned more about the counterfeiting scheme, including names of alleged participants, he summoned three of the most prominent lawyers in the colony, all of whom happened to live within a half mile of him in Williamsburg: Speaker of the House Peyton Randolph, Attorney General John Randolph, and Nicholas. They advised the governor to issue a warrant for the arrest of the suspects in far-off Pittsylvania County, have it served by local officers, and bring the suspects to Williamsburg to be examined. Five prisoners arrived at the capital on February 23 and were questioned by Peyton Randolph at the Governor's Palace. One was released. The others were given a hearing at the courthouse then taken to the gaol to await trial.

The Gaspée affair was too fresh on the minds of many burgesses, and too recently in Clementina Rind's newspaper, for them to miss the easy link between the royal governor's action in taking suspects from their home in Pittsylvania County for trial in Williamsburg and the Commission's power to remove suspected culprits to England. To many of those in the capital for the legislative session, the same British liberty was under threat and from the very same ministerial source.

Patrick Henry was particularly troubled by the similarities between the counterfeiting arrests and the Gaspée Commission. After all, it was Henry who, in 1769, had drafted Virginia's protest of a Parliament's proposal to transport colonial suspects to England for trial on treason charges. When the House formally convened for its session on March 4 and learned the news of the counterfeiting scandal, Henry and fellow burgess Richard Bland demanded a full investigation into the matter. Two days later Henry went to the Governor's Palace at the head of a delegation of burgesses to request from Dunmore a complete statement of the proceedings involving the arrest of the Pittsylvania counterfeiters. On March 11, the House adopted a resolution introduced by Henry and Bland that protested the governor's action.

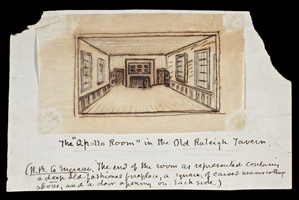

Henry and his fellow radicals had bigger plans to address the executive assaults on constitutional liberties than a mere resolution. That night, Henry met Richard Henry Lee, his brother Francis Lightfoot Lee, Thomas Jefferson, and Dabney Carr in a private room at the Raleigh Tavern, where the radicals reflected on what they saw as their country's perilous situation. The Gaspée affair revealed to them that the rights they enjoyed, the British constitutional liberties that were the foundation of their happiness, were under threat by the tyranny of the British government. If the Pittsylvania matter was a reliable indicator, Jefferson believed that the "old and leading members" of the House, like Randolph and Nicholas, were not "up to the point of forwardness and zeal which the times required." He later recalled of that night, "We were all sensible that the most urgent of all measures was that of coming to an understanding with all the other colonies, to consider the British claims as a common cause to all, and to produce a unity of action."

It was probably Richard Henry Lee who suggested to the group the creation of a system of intercolonial committees of correspondence to foster political cooperation. They left the tavern that night having drafted a resolution creating a standing committee of correspondence. Carr, Jefferson's brother-in-law and best friend, proposed the resolution on March 12, 1773, "with great ability, reconciling all to it, not only by the reasonings, but the temper and moderation with which it was developed." Henry and Richard Henry Lee also spoke in support of the resolution. An observer recalled, "I was not present when Mr. Henry spoke on this question; but was told by some of my fellow-collegians that he far exceeded Mr. Lee, whose speech succeeded the next day. Never before had I heard what I thought oratory; and if his speech was excelled by Mr. Henry's, the latter must have been excellent indeed. This was the only subject, that I recollect, which called forth the talents of the members during that session, and there was too much unanimity to have elicited the strength of any one of them."

The resolution was unanimously adopted. The committee's first order of business was a letter, dated March 19, from Peyton Randolph to the speakers "of the Different Assemblies of the British Colonies on the Continent." Randolph wrote, "I have received the commands of the House of Burgesses of this colony to transmit to you a copy of the resolves entered into by them on the 12th instant, which they hope will prove of general utility, if the other colonies shall think fit to adopt them. They have expressed themselves so fully as to the motives that led to these resolutions, that I need not say any thing on that point; and shall only beg you will lay them before your Assembly as early as possible, and request them to appoint some of their body to communicate from time to time with the corresponding committee of Virginia." Jefferson and Carr set out for home together after the governor prorogued the assembly, and agreed along the way that the result of the establishment of the committee would be, in Jefferson's recollections, the uniting of all the colonies "in the same principles and measures for the maintenance of our rights."

Dunmore gave the creation of the Virginia committee of correspondence less consideration than Hutchinson had given those of Massachusetts Bay. He informed the Secretary of State for the Colonies, "there are some resolves which show a little ill humor in the House of Burgesses, but I thought them so insignificant that I took no matter of notice of them." Richard Henry Lee had a very different view of the committee's import. On April 4, 1773, he wrote to the man to whom he had broached the idea five years earlier, stating to John Dickinson that the Virginia assembly "adopted a measure which from the beginning of the present dispute they should have fixed on, as leading to that union and perfect understanding of each other, on which the political salvation of America so eminently depends." Lee added, "You will observe, sir, that full scope is given to a large and thorough union of councils" and expressed his hope that "every colony on the continent will adopt these committees of correspondence and enquiry."