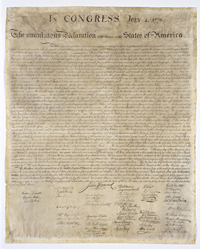

Declaration of Independence

The story of the Declaration of Independence began in earnest on May 10, 1776, when the Continental Congress adopted a resolution drafted by John Adams and moved by him and Richard Henry Lee to urge each of the colonies in rebellion to constitute new governments. Five days later, on May 15, the Fifth Virginia Convention, meeting in Williamsburg, agreed to instruct their delegates in Congress to introduce a motion for independence from Great Britain and moved forward with drafting a new constitution. On June 7, Virginia's Richard Henry Lee rose in the Continental Congress to propose "that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states." Because only eight of the 13 colonies were then on record as supporting independence, several days later the Congress agreed (by a vote of 7 to 5) to postpone consideration of Lee's resolution, appoint a "Committee on Independence" to draft a statement that explained why independence was necessary, and then recessed until July 1, when it was understood they would vote on Lee's proposal.

The Committee on Independence, otherwise known as the "Committee of Five," was comprised of John Adams, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson. It was determined by the committee that Jefferson would write the first draft (Adams' and Jefferson's later accounts differ on the manner in which the committee reached that decision, but the end result was the same). It took Jefferson several weeks to draft a document that relied heavily on Virginia's Declaration of Rights, largely the work of George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee, which was adopted by the Virginia Convention on June 12. It stated that "all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights…namely the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety." Drawing on a variety of intellectual sources — from seventeenth-century English commonwealth writers, to the authors of the Scottish Enlightenment, to the works of the French philosopher Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu — Jefferson crafted a document that was intended "to assert, not to discover truths." He therefore set out the case for American independence based on the "sacred & undeniable truths" that "all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness." He then described the "long train of abuses & usurpations" committed by George III that made the break with Great Britain not only necessary, but also reasonable. Among the more than two dozen charges, Jefferson held the King personally responsible with "imposing taxes on us without our consent," as well as for waging "cruel war against human nature itself" by enabling the institution of slavery.

Jefferson then submitted his draft to Franklin and Adams, the two committee members whose opinions he respected most. They made several, mostly stylistic changes to the document that made clearer and more direct the few awkward passages in Jefferson's prose. For example, "sacred & undeniable truths" became simply "self-evident," and "from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable" was rewritten as "they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights." Substantively, however, the document remained almost entirely Jefferson's when it was presented to the Continental Congress on July 2, immediately after 12 of the colonies (New York abstained) voted to adopt Lee's resolution for independence. The delegates then spent the next two days debating and revising Jefferson's declaration. The most important change to the document was the removal of his condemnation of slavery, which was required to secure the support of the Carolinas and Georgia. The revisions displeased Jefferson so much that he made sure to send copies of his original draft to friends in Virginia, one of whom remarked that Congress "altered it much for the worse." Nevertheless, the editing process was completed on the morning of July 4, when the declaration was adopted, signed by the president of Congress, John Hancock, and its secretary, Charles Thomson, and ordered to be printed (which became known as the "Dunlap copies" after the name of the Congress' official printer) and distributed to the colonial assemblies and to the Continental Army.

The Declaration of Independence reached Williamsburg in time for its concluding paragraphs, which declared the United Colonies "FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES," to be printed in Alexander Purdie's Virginia Gazette on July 19. The full text was published the next day in Dixon and William Hunter's rival Virginia Gazette. In New York at the end of July, the Rev. James Madison, a Virginian, wrote to a friend in London that "An independency is…certainly declared, all possibilities of treaty is therefore at an end. The die is cast." The declaration arrived in London only several weeks later and was printed first in the Public Advertiser on August 16, shortly after news of the "amazing Height of Madness" that gripped Virginia in its declaration of independence from Great Britain.

The document itself was engrossed in its final parchment form on August 2, which is when most of the delegates signed it. Six delegates, including Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe, signed it later, while two, John Dickinson and Robert Livingston, declined to sign it at all.