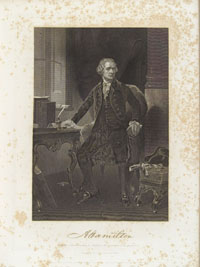

Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804)

Alexander Hamilton was an officer in the War for Independence, America's first Secretary of the Treasury, and credited by many historians as the architect of its financial system. As a particular favorite of George Washington's, Hamilton played a crucial role in the nation's founding, starting with his youthful service in the Continental Army until his 1804 death in a duel with Aaron Burr.

Hamilton was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis, the second of two illegitimate sons to Rachel Faucett Lavien and James Hamilton, an itinerant Scottish merchant (Hamilton later gave his birth date as 1757, but many scholars now believe he was born two years earlier). His father abandoned the family in 1765 and his mother died of yellow fever in 1768. Fortunately for Hamilton, he was gifted with a mind for figures and managed to secure an apprenticeship with a merchant house that he was soon running. In 1772, Hamilton's talents inspired his minister, Hugh Knox, to initiate a public collection to send him to college in America. After spending some time at Elizabethtown Academy in New Jersey, he entered King's College (now Columbia University) in New York in 1774. He thrived in the intellectual atmosphere at school but struggled with mathematics. To catch up Hamilton sought private lessons with a Scottish mathematician, Robert Harpur, who provided him with a strong foundation in financial formulas that would later become instrumental during Hamilton's government service. He also honed his writing skills and began publishing anonymous articles in support of the Patriot cause in the local newspaper, along with two pamphlets.

In March 1776 he left college to serve as captain of an artillery company he helped organize. Hamilton's intelligence and skill in battle quickly caught the attention of his superiors and in January 1777 George Washington invited him to join his staff as an aide-de-camp. Promoted to lieutenant colonial, Washington became increasingly reliant on Hamilton's administrative talent, which kept the two together until February 1781 when Hamilton, earnestly desiring the glory that came with battlefield heroics, left Washington's staff. In July he sought to return to the army with a field command but Washington denied his request, leading Hamilton to resign his commission. Washington later relented in time to give Hamilton command of a key assault on a British redoubt at Yorktown on the night of October 14, 1781. Hamilton then left the army again to return to his wife in New York and there to study law. He passed the bar in 1782 and began a flourishing legal career.

An avid polemicist, Hamilton wrote a series of essays between July 1781 and July 1782 in which he advocated the replacement of the Articles of Confederation with a strong federal government. In 1782, he was elected to a single term in the Continental Congress, and in 1786 he joined the New York Assembly for a term. Hamilton was then appointed him one of New York's representatives to the Annapolis Convention, at which he drafted the resolution calling for a convention to reform the Articles of Confederation. A delegate to what became the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in May 1787, Hamilton aggressively advocated a system of government based on a republican version of the British constitution (as Hamilton, somewhat imperfectly, understood it). Branded a monarchist, Hamilton rarely attended the convention after that, although he did return to sign the final document.

Hamilton's greatest contribution to the Constitution may well have come with his part in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays co-authored by James Madison and John Jay (although Hamilton wrote the majority of them) intended to counter arguments against ratification. He also played a leading role in New York's ratifying convention, a job that became much easier when news reached the delegates on July 2, 1788, that Virginia's convention had approved the Constitution. New York did so on July 26.

After Washington was elected president, he invited his former protégé into the administration to serve as America's first Secretary of the Treasury, an office seemingly tailor made for Hamilton's particular talents. Given his personal closeness with Washington, Hamilton assumed a degree of power in policymaking that frightened his colleagues, such as Thomas Jefferson, who became his political rivals and then his enemies. Hamilton's reports on credit and manufacture led to establishment of the Bank of the United States, a centralized federal debt, and the creation of a national securities market. He left the Cabinet in January 1795 to return to the practice of law, yet he remained uniquely influential with Washington, going on to write the president's last annual message to Congress, as well as much of Washington's "Farewell Address."

Hamilton's enemies caught up with him when they published charges that as Secretary of the Treasury he had made blackmail payments to James Reynolds to cover up irregularities with public finances. Always highly sensitive to threats to his honor, Hamilton's 95-page response actually did more harm to his reputation than the original charge: He admitted to the blackmail but explained that its purpose was to cover up an affair with Reynolds' wife, not a misuse of Treasury funds. Washington, ever loyal to his "family" of former aides, did not let Hamilton's disgrace stand in the way of persuading John Adams (much against the president's inclination) to appoint Hamilton a major general and second-in-command, to Washington, of an army raised to counter a looming, but ultimately avoided, French invasion. Hamilton could not let Washington's apparent attempt to rehabilitate him in the public eye stand, however, as he proceeded to rancorously oppose Adams' re-election in 1800 with virulent newspaper attacks that called into question the president's very sanity-and Hamilton's own judgment. He then threw his support behind a man he loathed, Thomas Jefferson, rather than see a man he hated even more, fellow New Yorker Aaron Burr, become the next chief executive.

The antipathy toward Burr continued with Hamilton's efforts to keep Burr from becoming New York governor in 1802 and a set of insulting remarks about Burr that Hamilton uttered at a private dinner and refused to retract. Their personal conflict escalated into the most famous duel in American history, between the sitting vice president and the former secretary of the treasury. The two enemies met on a cliff at Weehawken, New Jersey, on July 11, 1802 (where Hamilton's son had been killed in a duel in 1799). Hamilton missed, Burr did not. Hamilton died of his wounds the next day.