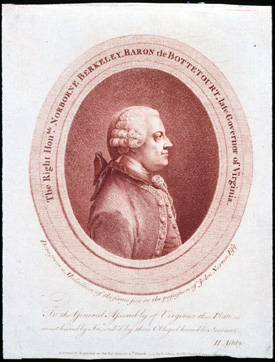

Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron de Botetourt (ca. 1717-1770)

Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron de Botetourt, was royal governor of Virginia from 1768 to 1770. He was born about 1717 in Stoke Gifford, Gloucestershire, to John Symes Berkeley and Elizabeth Norborne. His political career began in 1741 when he was elected to Parliament, where he remained until 1763 when he left the House of Commons to pursue a seat in the House of Lords through the Barony de Botetourt, a title that had lain in abeyance since 1406. Berkeley's fortunes rose on the accession of George III: he was appointed a Groom of the Bedchamber in 1760, named Lord Lieutenant of Gloucestershire in 1763, and in April 1764 his petition for the Barony was confirmed. He took his seat in the House of Lords as the first Baron de Botetourt in almost 400 years.

Botetourt ruined his fortune in a failed mining project in the 1760s. His political allies in the British government (Lord Bute chief among them) found a job for him as governor of Virginia, beginning July 29, 1768. What popularity he had can be traced to his remarkable talent for simultaneously appearing to be different things to different people. He told Virginians, for example, that he was toiling to defend their rights in London at precisely the same time he was calling on Lord Hillsborough, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, to crush them. Botetourt's slipperiness was well known in England by the time he was appointed Virginia's governor, displacing the well-respected Sir Jeffrey Amherst. The arch-polemicist "Junius," in one of his famous newspaper essays, called Botetourt "a cringing, bowing, fawning, sword-bearing courtier." The author recalled Botetourt's shift from a supporter of the loyal opposition with George Grenville when he was merely Norborne Berkeley, to attacking the opposition on behalf the government after its approval in 1764 of his claim to the Botetourt title. Seeing Botetourt shortly after his appointment to the Virginia governer's position, Horace Walpole said "the disquiets in America" required sensible leaders to calm them, especially in Virginia, which "though not the most mutinous, contains the best heads and the principal boutefeux." Walpole highly doubted that Botetourt, whose genial countenance he thought little more than a screen for more devious intentions, was the right man for the job. Walpole observed that "To Virginia he cannot be indifferent: he must turn their heads somehow or other. If his graces do not captivate them, he will enrage them to fury; for I take all his douceur to be enamelled on iron." But Botetourt had enough support in London for him to be on a ship headed to the Chesapeake within three weeks of his nomination.

His popularity soared in Williamsburg. Many Virginians believed that Botetourt was the right man at the right time, a governor with the wisdom and influence to act as a transatlantic protector of their interests against the British Parliament's encroachments. Even dissolving the Virginia assembly could not harm his reputation, as John Page reported to a friend in London in May 1769: "This has not lessen'd him in their Esteem, for they suppose he was obliged to do so; he is universally esteemed here, for his great Assiduity in his Office, Condescension, good Nature & true Politeness." What Page did not know was that just as he was writing his letter, the governor took the opposite tack in a letter to Lord Hillsborough, saying, "that Opinions of the Independancy of the Legislature of the Colonies are grown to such a Height in this Country, that it becomes Great Britain, if ever she intends it, immediately to assert her Supremacy in a manner which may be felt." Botetourt observed that parliamentary acts were useless in the face of colonial obstinacy and told Lord Hillsborough "to loose no more time in Declarations which irritate but do not decide."

Botetourt's announcement about the repeal of the Townshend Duties further aggravated transatlantic misunderstandings. He pledged to the Virginians "that I will be content to be declared infamous, if I do not...exert every power...to obtain and maintain for the continent of America that satisfaction which I have been authorized to promise this day by the confidential servants of our gracious Sovereign" that the taxes would be removed. The Virginians seized on the statement, responding that "We esteem your lordship's information not only as warranted, but even sanctified by the royal word." Botetourt's declaration seemed to confirm rising paranoia that "confidential servants" were secretly calling the shots in Westminster, and his failure to mention Parliament perpetuated the constitutional myth that the Crown had a meaningful role in deciding colonial policy, especially in financial matters.

The most intense reaction to the governor's speech was heard on the floor of the House of Commons in May 1770 from that master of the sublime, Edmund Burke. "I really cannot read this without emotion," Burke proclaimed as he pointed to a copy of Botetourt's remarks. "Have we been sent here to see the business of parliament settled by the King's confidential servants?" He said it was ludicrous to praise the Crown for steps that could be taken only by Parliament and pointed out that fostering such misunderstandings of parliamentary authority would only make the situation more unstable.

Botetourt served in Virginia only two years, dying in Williamsburg on October 15, 1770, after an illness lasting several weeks. He was buried in the crypt of the Wren Chapel of the College of William & Mary. He never married and left no direct heirs.