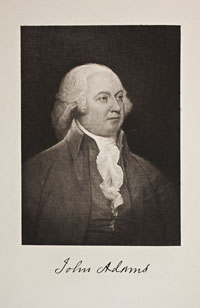

John Adams (1735-1826)

John Adams was second President of the United States (1797-1801), twice Vice President of the United States, and a member of both the First and Second Continental Congresses. Born in Braintree (afterward named Quincy), Massachusetts, Adams studied law at Harvard. He married Abigail Smith in 1764, and they had five children.

Attracted to the patriot cause at the time of the Stamp Act turmoil, John Adams was later elected a Massachusetts delegate to both Continental Congresses. On his recommendation, George Washington was made commander-in-chief of the Continental troops — a move that helped bind Virginia to the intercolonial cause for independence. During the Revolution, Adams went to France and Holland as a diplomat and helped to negotiate the Treaty of Paris in 1783 to formally end the War for Independence. From 1785 to 1788 Adams was United States envoy to Great Britain and afterward served as Washington's Vice President (1789-1797).

Adams's presidential administration was politically tumultuous, marked by turmoil in post-Revolutionary France. War between the French and British caused great difficulties for the United States on the high seas and intense partisanship among factions within the U.S. The French government wanted support from its former ally in war against Britain and was willing to use force to persuade the United States to join the conflict. Adams almost single-handedly averted a war in 1798 between France and the United States after the XYZ Affair. But he also signed into law the legislation known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, forced through Congress by the Federalists to tighten control over immigrants and anyone who criticized the government. Adams did not originate the Acts but became associated with these unpopular measures in the public mind. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison defined the opposing position in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions.

When Adams retired from public life in 1801, he and Abigail returned to Quincy and lived quietly. His pen never ceased writing — either friendly letters or severe political statements — until his death on July 4, 1826, a few hours after Thomas Jefferson drew his last breath.