The Credit Crisis of 1772

Just as the Sugar Act of 1764 had a disproportionately negative impact on New Englanders, and substantially contributed to their negative opinion of imperial commercial regulation, the Credit Crisis of 1772 hit hearts, minds, and pocket books in the Chesapeake especially hard. Once the non-importation associations created to protest the Townshend duties disappeared, British credit flowed back into Virginia and Maryland, along with British goods. Virginia, however, was in a particularly precarious economic position, especially after the Great Fresh of 1771, described by one Virginian, Robert Carter Nicholas, in June 1771 as "a dreadful & pretty general Calamity which has happen'd by cast Floods of water issuing down from the mountains." The massive flooding carried away tobacco, buildings, and a number of lives, causing more than £30,000 in damage. The event was of such significance that another Virginian, Ryland Randolph, noted on a monument he erected that year (and which still stands) that "the foundation of this pillar was laid in the calamitous year 1771: when all the great rivers of this country were swept by inundations never before experienced."

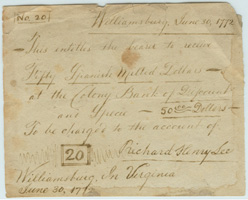

In London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow at the same time there was a quite different sort of calamity brewing among some of the largest, mostly Scottish, merchant houses. Having extended their credit too liberally to colonial planters unable-or, in not a few cases, unwilling-to pay, nervous bankers and others began to stop payment on the bills of exchange that circulated around the world as the primary means of transatlantic currency exchange. Alexander Fordyce was the first to go and other houses began to fall like dominoes as one house after another began to refuse payment on bills and plead with colonial debtors to pay their bills in cash and coin. As one London observer in the Virginia trade described to a friend in India, "inumerable are the Failures that have happened in this City & at Edinb[urgh]." The mounting bankruptcies "like a thunder Storm has tumbled to pieces carrying desolation & destruction along with it."

Broadly speaking, the imperial credit markets would never properly recover (subsequent non-importation agreements would provide a final blow to the surviving merchants, eliminating whatever political sympathies they retained for their colonial connections). To hang on, merchant houses were forced to tighten their credit strings and insist on stricter terms with their account holders, many of whom were in the Chesapeake, implementing tighter business practices that remained in place for the remainder of the colonial period, and which therefore increased in odiousness to large, middling, and small planters alike who dealt mainly with Scots houses that were dependent on the openness of European markets and a monopoly on providing tobacco to France (which had been understandably interrupted during the Seven Years War). Such planters, mainly in Maryland and the Virginia Piedmont, felt more pressure to pay and grew in opposition against attempts by the merchants to close loopholes that allowed them to avoid it.

Even in the Chesapeake tobacco markets, however, the Credit Crisis of 1772 did not impact everyone equally. Virginia Tidewater planters who consigned sweet-scented tobacco to the British market, and the English firms with whom they maintained long-term relationships, many going back several generations, remained afloat. None of the major sweet-scented firms went under, sparing Tidewater planters and their allies the brunt of the crisis and the disaffection with imperial commercial policy that followed.