Pontiac's Rebellion

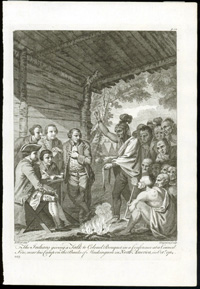

Named for a leader of the Ottawa, Pontiac's Rebellion (sometimes known as Pontiac's War or the "conspiracy of Pontiac") amounted to a continuation of the Seven Years War by Native American enemies of the British. Once the French threat was removed from North America, the British commander-in-chief of North America (and Virginia's governor), Sir Jeffrey Amherst, put an end to traditional diplomatic gift-exchanges with Native Americans and sought to place major restrictions on trade with them, such as prohibiting weapons and gunpowder. Such measures fueled Native American apprehensions created by the withdrawal of the French from America, which, in the minds of many wary Natives, left the British without any sort of check on their expansion or authority. At the same time, a major philosophical movement—inspired by Neolin, a Delaware prophet—was spreading among Native peoples that stressed self-reliance and moral improvement by disconnecting oneself from European, mainly British, goods. Neolin also called for the ouster of the British, whom he called the "dogs clothed in red," from their lands. The fighting began on May 7, 1763 when Pontiac, inspired by Neolin's vision and hoping for the return of the French, laid siege to the British fort at Detroit while other Native forces attacked posts and settlements throughout the Ohio country. The siege of Detroit lasted for six months, until Pontiac learned of the Treaty of Paris. He withdrew on November 10, 1763. By the end of the year, almost every British fort in the northwest had been destroyed and perhaps 2,000 colonials had been killed in the western reaches of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. Sporadic fighting continued for another several years, until Pontiac signed the Treaty of Oswego in July 1766, but widespread resistance to the British dwindled in the wake of a substantial reconsideration of their Native American policies.

One major result was the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which, at least in principle, put a limit on colonial expansion into Native territories. Another consequence was British disappointment at the failure of colonial governments to provide troops to aid in their common defense. The Virginia assembly, for example, refused to allow its militia beyond the borders of its province.