French and German Protestants in British America

French Protestants

From the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth centuries, French Calvinists known as Huguenots fled Catholic France to neighboring countries such as the Netherlands and England to escape religious persecution under Louis XIV. Some 50,000 Huguenots settled in England between 1685 and the early eighteenth century after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes that had guaranteed French Protestants peaceful coexistence with Catholics and improved civil rights. Huguenots brought with them highly developed skills in textiles, silversmithing, and other trades and in professions such as law and education. The refugees joined existing French congregations or formed new ones under changing policies during England's own religious upheavals. The situation eased after William III became king in 1688, and Protestant succession to the English throne was secure. Although Huguenot worship differed from Anglican practice and the language barrier had to be overcome, the refugees assimilated fairly quickly into the Church of England.

The first Huguenots arrived in Virginia in 1700. Governor Francis Nicholson greeted the 207 refugees, and Virginians received them with kindness. Colonial officials used the Huguenots as a means to clear land and act as a buffer between civilization and the Indians to the west. Instead of settling them at the border of Virginia and North Carolina, as originally planned, they were relocated to Manakin, the site of an extinct Monacan Indian village near present-day Richmond. Over 400 followed the first settlers to Manakintowne within the same year settling in a 10,000 acre grant along the James River given to them by King William. Manakintowne became the largest French settlement in America. They soon conformed to the established Church of England. In 1704 they petitioned and received naturalization by the Virginia Assembly. Virginia authorities organized Huguenot refugees into their own parish (King William, after their benefactor). Their minister, Monsier De Joux, had been ordained an Anglican priest in England. At first these communities sought and received the Anglican Book of Common Prayer translated into French. Within a few years, French congregations blended seamlessly with the larger Anglican church in Virginia.

German Protestants

The great immigration of Germans into the American colonies began when William Penn, after having received his charter of the province of Pennsylvania, visited the Rhine region (also known as the Palatinate) and, speaking to refugees from that war-devastated section in their own language, invited them to find new homes in America.

In Virginia, the German Reformed Church had its beginnings in a small group of workmen whom Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood imported to develop and carry on his iron mines and furnace at Germanna in 1714. The German Reformed Church in Virginia looked back to the block house in the center of the fortifications at Germanna as its first place of worship. Explorer John Fontaine, who visited Germanna in 1716, wrote: "They go to prayer constantly once a day, and have two sermons on Sunday...They seemed to be very devout, and sang the Psalms well." Upon the end of their indenture they moved as a group to Germantown in Fauquier County. Up until the Revolution, Germantown was a prosperous farming community consisting of a village, church and school. The population gradually moved away and children intermarried with English families. In 1733 a Reformed settlement had sprung up on the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains in present-day Loudoun County. Settled by a colony of Germans from Pennsylvania, the Congregation still survives today at Lovettsville. The first known German Reformed settlement west of the Blue Ridge was organized in 1740 at Kernstown.

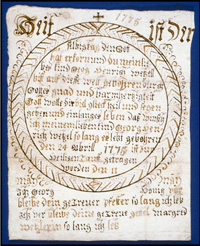

Like the German Reformed Church, the roots of the first Lutherans in Virginia are found at Germanna. The first group to arrive at Spotswood's iron works was also in 1714, followed by a second wave in 1720. When their indentures were up, both groups moved as a whole up the Rapidan River and settled in present-day Madison County, Virginia. In 1725 they organized Hebron Congregation, the first and oldest Lutheran congregation in America, which was assisted by financial aid from Germany. "Within a circle of a few miles," wrote a visitor to Hebron in 1748, "80 families lived there together, Lutherans, mostly from Wurtemburg. They have a beautiful large church and school, also a parsonage and glebe of several hundred acres." In contrast to the well-organized Hebron community, the Lutherans who settled in the Shenandoah Valley and Hampshire County in 1727 worshipped in private houses and erected crude log buildings for schools. Up to three-quarters of the population in the Shenandoah Valley is believed to have been German. Due to convenience and common language, many Lutherans and Reformed Germans worshipped together. The sermon, which was set in a framework of a vernacular liturgy, was the main part of Lutheran worship. Communion was rarely given, and as they had no permanent Lutheran minister to administer the sacraments, they had to rely upon occasional visits of a minister of some acceptable denomination.

The first settled Lutheran pastor to the Valley was Peter Muhlenburg, son of Henry Muhlenburg, the founder of Lutheranism in America. Muhlenburg arrived at Woodstock, Virginia in 1772 as parish minister. Remarkably, though schooled in Lutheranism, Peter was never ordained in that ministry. Instead, he was ordained in the Anglican Church so he could attend to the needs of both the Germans and English in his parish, as well as to gain the benefits of an Anglican minister. Muhlenburg was elected to the Virginia Legislature in 1774 and was present at St. John's Church when Patrick Henry gave his immortal cry of "Liberty or Death!" Returning home, Peter gave his final sermon in similar fashion. After reading from Ecclesiastes 3:1, Muhlenburg threw off his robes to reveal a military uniform underneath. He enlisted his congregation, known as "The German Regiment," and served as their commander during the Revolutionary War.