Role of the Press in the Gaspée Affair

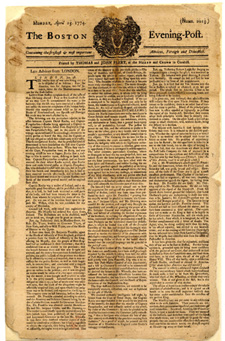

The Boston Evening-Post, April 25, 1774

The creation of the Gaspée Commission was chronicled in newspapers throughout the colonies. But more than just reporting the news, colonial newspapers influenced political opinion and action by publishing polemics that attacked the actions of the Gaspée Commission and called for intercolonial unity. The most important and striking example of the influence of colonial newspapers in the wake of the Gaspée Affair occurred in Virginia, where the Virginia Gazettes' coverage of the Affair played a seminal role in that colony's creation of the system of intercolonial committees of correspondence.

The Gazettes encouraged this reaction by printing unreliable news and polemics related to the Gaspée Affair and Commission. First, the Gazettes shared with every other colonial newspaper an inherent unreliability that led Virginia's leaders to create an alternative communication network, an intercolonial "circle of trust," to ensure the accurate and timely transmission of pertinent information. Second, the persuasive pieces printed in the Virginia Gazettes in the first months of 1773 influenced Virginians to believe that the Gaspée Commission threatened their right to trial by a jury of their peers, a cherished constitutional liberty. More importantly, they also reinforced the idea that Virginia's interests were intimately connected to those of Rhode Island and the other colonies. In these ways, the Virginia Gazettes did not merely report the news in 1773, they helped create it.

However, Virginians who followed coverage of the Gaspée Commission were misinformed from the beginning. On January 7, 1773, Alexander Purdie's Gazette ran a rumor that British ships and troops were moving to Rhode Island from New York. Purdie also included ominous, and false, word that "a Motion was intended to be made, the next Session of Parliament, to have the Charter of [Rhode Island] vacated" Charter rights were held as so sacred on both sides of the Atlantic that even the hint of a threat to those rights was enough to send many colonials into paroxysm.

Accurate information surrounding the creation of the Gaspée Commission finally reached Virginians on January 21. Clementina Rind joined Purdie in carrying word from Boston that "a Commission came by the Cruiser, under the Great Seal," appointing Joseph Wanton, the elected governor of Rhode Island; Daniel Horsemanden, New York's Chief Justice; Peter Oliver, Massachusetts's Chief Justice; and Robert Auchmuty, a judge of the Admiralty Court, "to make Inquiry into the Affair of burning his Majesty's Schooner gaspee."

Although accurate, the Boston account was distorted, liberally mixing commentary with facts: "If burning the Gaspee Schooner was a Matter of serious Importance, much more so are the Methods pursued by the British Administration in Consequence of it." Any persons accused of committing the crime "are to be apprehended, and, together with the Evidences, sent to England for trial." The power of the commission was not a threat merely to Rhode Island, but was an "Indignity offered to all the Colonies." To crystallize the danger to liberty posed by the commission for readers in places like Virginia, the writer of the article invoked the specter of the Boston "Massacre." Massachusetts, "having themselves tasted the Cup of ministerial vengeance," knew well what was now happening to the people of their neighboring colony, and asked what would stand in the way of "the like Scene of Blood, Rapine, and Slaughter" if the commission called on troops to enforce its will. "Such treatment of the Colonies," the author warned, "calls for the most serious Attention."

The same edition of the papers gave Virginians more reason for vigilance with news from Providence regarding "the very extraordinary Measures adopted by Government for inquiring into the Matter" of the burning of the Gaspée. Again, though this item provided basically accurate information, its objective value was undermined by the strident rhetoric attached to it. The Providence writer reiterated the commissioners' power to call in troops and to send suspects to England to "be tried for High Treason." While not as hyperbolic as the dispatch from Boston, the author, in only slightly more measured language, noted, "every Friend to our violated Constitution cannot but be greatly alarmed." He went on to paint a dire picture of the issue at stake for all colonists, not just the people of Rhode Island: "The idea of seizing a Number of Persons, and transporting them three Thousand Miles for Trial, where, whether guilty or innocent, they must unavoidably fall Victims alike to Revenge or Prejudice, is shocking to Humanity, repugnant to every Dictate of Reason, Liberty and Justice, and in which Americans and Freemen ought never to acquiesce."

Word from England was added to such accounts when Purdie printed a letter from a Gentleman of Character in England to his Friend in Boston. "Our Tyrants in Administration are greatly exasperated with the late Manoeuvers of the brave Rhode Islanders," the author wrote. As if in confirmation of the false rumor that appeared in the paper two weeks earlier, he wrote that "the present wretched Conductors of the Whole of Government" were planning to vacate Rhode Island's charter and apprehend suspects by armed force if necessary. He was sure to provide a memorable mental image to help his readers know exactly what the British government was doing to them. In the face of "bitter Pills . . . to be crammed down their Throats," the colonists must "[b]e united, our dear suffering Brethren, be steady, and Success awaits you; Freedom, glorious Freedom, will be the Purchase." The writers' point was clear: the threat to colonial liberties was severe; united opposition was the only answer.

Eschewing the printing of the more radical hyperbole that colored the facts of the Gaspée Affair, Purdie carried nevertheless ominous information from Newport that the commissioners had arrived to begin their work along with "the Mercury Man of War, Captain Keeler, of twenty four guns," and four other ships. He also included an extract of a letter from Willam Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, to Rhode Island's governor that spelled out the commission's powers. But Purdie also included a snippet of news that was more startling, and more inaccurate, than anything written by the radicals: On an inside page was a false report from New York that a battle had taken place between colonists and British troops sent to support the Gaspée Commission. Six Rhode Islanders were reported dead and eighteen wounded.

Such less than reliable coverage of the Gaspée Affair laid the foundation for Virginia's reaction to the creation of the Gaspée Commission and the creation of the intercolonial committees of correspondence.