The Stamp Act

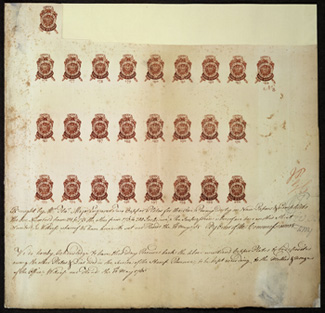

Proof sheet of stamps, Philatelic Collection, The British Library

The Stamp Act, ratified by royal assent on March 22, 1765, had been under consideration since September 1763 and was first introduced in the House of Commons in March 1764. It applied to the colonies a stamp tax on all sorts of paper—from newspapers to legal documents to playing cards—that had been in place in England for more than a century. First Minister George Grenville had the measure withdrawn when an objection was raised that the colonies should be consulted. He therefore postponed it to give the colonies time to respond and propose alternatives. Although colonial agents in London, such as Benjamin Franklin and George Mercer, assured him that Americans would accept a stamp tax on newspapers, legal and shipping documents, and a few other items, Grenville's plan was greeted with protests. In the summer of 1764, the Virginia legislature's Committee of Correspondence directed their agent in London to "insist on the Injustice of laying any Duties on us and particularly taxing the internal Trade of the Colony without their Consent." Paying the duty would also be a heavy burden to the people because they were "already laden with debts."

In January 1765, Grenville made an offer to the Americans: the stamp duty would be laid aside if they proposed another mode of raising the funds. Colonial agents in London rejected the offer out of hand, following the instructions of their assemblies to question the right claimed by Parliament to tax the colonies at all. Without an alternative, Grenville re-introduced the bill on February 6, 1765. Except for a memorable exchange between William Legge, the Earl of Dartmouth, and Isaac Barré, the bill passed the House of Commons the next day "almost without debate" (according to a contemporary historian), by a vote 205-49. It was scheduled to go into force at the beginning of November.

Colonial resistance to the act was so pervasive and direct that, when Parliament met for its next session on January 14, 1766, influential members such as William Pitt demanded the Stamp Act's repeal, which was accomplished two months later on March 18, 1766. Its retraction, however, was coupled with passage of the Declaratory Act, which asserted Parliament's power "to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever." Nevertheless, the repeal was hailed throughout the colonies as it was in Williamsburg in June 1766, where a "ball and general illumination" was held in celebration.