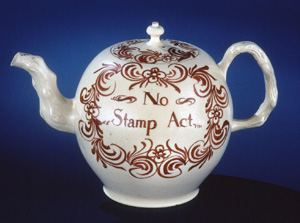

The Stamp Act Crisis

The passage of the Stamp Act was met with widespread resistance in the colonies. The most virulent of the colonial reactions were the seven Stamp Act Resolves introduced by Patrick Henry in the Virginia House of Burgesses on May 29, 1765. They echoed the stance taken by writers and speakers in other colonies (and in Virginia in 1764) with their strong denial of Parliament's authority to tax the colonies. Henry's language, however, was especially direct, calculated to enlist the understanding and support of average colonials. The Resolves unambiguously declared that "every Attempt to vest" the power of taxation anywhere but the Virginia assembly "has a manifest tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom." In far off Massachusetts Bay, its governor, Sir Francis Bernard, wrote that Henry's resolves sounded "an alarm bell to the disaffected." British ministers, however, believed that the disaffected were only a small, misled segment of the American population. Secretary of State Henry Seymour Conway, for example, wrote in October 1765 that resistance to Parliament's authority "can only have found place among the lower & more ignorant of the People" in the colonies.

Conway could not have been more mistaken. By the time that agents, such as Virginia's George Mercer, arrived in America with the stamps in October, the political atmosphere in the colonies was almost universally toxic. Representatives from nine colonies met in a Stamp Act Congress in New York that month and adopted John Dickinson's Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which stated that an essential component of British freedom was to be taxed only with one's own consent, which rested in the provincial assemblies. Some colonials were inclined to more extreme measures. In Boston, for example, the "Loyal Nine"—a secret group of merchants and artisans—decided that physical violence should be used to stop the use the stamps. On October 30, 1765, Mercer had to be rescued from an angry mob in Williamsburg (he resigned his duty and soon left to return to England). William Holt, a Williamsburg merchant, wrote to a friend in Boston, "We are as violent opposers of ye Stamp Act here as you in New England and will never submit to ye Chains." Because of the widespread resistance, only in Georgia did the Stamp Act actually go into effect.